The Politics is criminal,

not the people

FAQ

Smuggling is defined as unauthorized transport across borders. Contrary to human trafficking, smuggling occurs with the consent of the persons being transported. Seeking asylum is a basic right and therefore legal in Europe. An application for asylum can only be made in the country of arrival. However: For the large part of People on the Move any possibilities to enter Europe legally are non-existent. Europe must therefore be reached via illegalized routes - such as the Mediterranean or the so-called Balkan route - in order to submit a legal application for asylum in the territory. On their way, persons are again dependent on smugglers, who streamline the process and sell their services to (at least in theory), assist in avoiding direct harm.

The answer to the question should be: always. But the reality looks different. While Europe perceives some persons as humanistic helpers, it criminalizes others as smugglers. In both cases, smugglers are human beings. Individuals who are forced to put themselves in life-threatening and exploitative situations are often portrayed as brutal and inhumane. The demonized image that European politicians and mainstream media paint of most smugglers only contributes to criminalizing those who aid in smuggling, rather than scandalizing the brutal and inhumane border and migration policies. Persons are criminalized for helping each other in life-and-death situations. They are imprisoned because they acted in solidarity.

Criminalizing persons in the course of their own migration, has become part of Europe's policy of deterrence. Persons who flee usually have no alternatives. If there were safe passages, people would make use of them, rather than having to take on undignified, exploitative, and life-threatening work.

Criminalizing the act of smuggling persons does not fight the global injustices that underlie the reasons why people flee their country nor does it fight migration. It only turns persons who are fighting for their lives by being forced to flee, first into involuntary smugglers and then into "criminals." As a consequence, hundreds of persons end up in prisons every year, are forced to pay high fines, or sometimes serve life imprisonment.

Only those who perceive migration as a threat can benefit from "border security". Because "security" for some equals the elimination of others. Actual security is what People on the Move need, while Europe can offer protection.

The basis for the imprisonments is the Greek legislation, which states: every person who drives a vehicle with which persons enter Greece without valid residence documents is automatically subjected to being a smuggler. This law has allowed for placing culpability on the victims. Often times when a boat or car carrying migrants arrive in Greek territory, the local border guards arrest at least one person and accuse them of smuggling. This may be the person who held the rudder or tiller to steer the boat or the person who communicated with the Coast Guard to call for help. Sometimes it is simply a person who speaks English.

At the moment, migrants convicted of unauthorized entry make up the second largest group of persons in Greek prisons. A committee of the Council of Europe has recently described the conditions under which migrants are forced to live in these prisons as a violation of human dignity. As of September 2022, Greek prisons were housing up to 11,182 persons, with a maximum capacity of 10,175, leading to an average occupancy rate of 110 percent. In some prisons, overcrowding reached far higher numbers.

Korydallos Prison, where Homayoun Sabetara has been held since September 2021, had an occupancy rate of 152 percent at that time. Homayoun reported that for the duration of 16 months, he had to share a small room with up to 26 persons. Due to overcrowding, many inmates are forced to sleep on the floor without blankets or mattresses. There is a lack of hot water. The quality of food is poor (usually pasta without any sauce) and usually insufficient for the number of inmates.

The penal system in Greek prisons is unacceptable. Several reports have been published about inadequate equipment and the use of violence. Prisons are understaffed and provide limited to no access to medical services. Six years ago, Homayoun underwent cancer surgery and has had to take regular medication since then, but in prison, he has been unable to receive it for months. Since being detained in a basement prison with another 20 people, with hardly any air, he has suffered from breathing problems and coughing. However, he has yet to receive proper medical care, including glasses or basic necessary medications such as an asthma inhaler. For months now, he has not received any medical check-ups despite several complaints of pain caused by either sleeping on the floor or on very poor mattresses. His neck arthritis makes it difficult for him to be pain-free even when sitting.

Recent evidence by civil society and human rights groups shows that in countries such as Greece and Italy, basic fair-trial standards are often disregarded. Many persons are arrested immediately upon arrival in Greece. During the approximate one year of pre-trial detention, detainees typically remain without information about their case or legal assistance.

Record materials confirm that translation services are consistently denied, exculpatory evidence is ignored, and witnesses are not called to testify. The average court hearing lasts approximately 38 minutes and results in an average prison sentence of 44 years. In a large number of cases, maximum sentences ranging from 50 to 150 years imprisonment are applied, in others, fines of hundreds of thousands of euros are imposed. These sentences, proportionate to a specific number of years per person present in the car or boat, pose an impossible situation for thousands of innocent migrants. If a shipwreck took place, charges such as manslaughter may be added to the conviction. While it is possible to appeal these sentences, it requires legal assistance, money, and public connections to do so. If these three resources are available, it is quite possible for the case to be dropped or for an acquittal to be reached, as a number of cases in recent months have shown.

BLOG

JAN 2025

“Ants Became My Best Friends”

Interview with Homayoun Sabetara after his release from prison in Trikala – 06.01.2025, Thessaloniki

In August 2021, Homayoun Sabetara wanted to travel from Iran to live with his children in Berlin, but was arrested after having driven a car with seven other people across the Turkish-Greek border. One year later and in an unfair trial, he was sentenced to 18 years in prison for ‘people smuggling’. Despite a lack of evidence and a lengthy legal battle, his sentence was only reduced to 7 years and 4 months three years later on appeal. However, he was not acquitted. In Thessaloniki in early January 2025, he talks to Kiana Ghaffarizad, part of the #FreeHomayoun campaign team, for the first time after his release from prison about his experiences and wishes for the future.

Homayoun Joon, when you finally sat on the bus to Thessaloniki on December 16th: What was going through your mind during that ride?

First, it’s a pleasure to be able to speak with you today. Finally, after three years I have been released from prison. First and foremost, I want to express my deepest gratitude to the people involved in the campaign and to all those who tirelessly fight for others’ rights.

On that day [December 16th], first, the private police took me to Trikala to the police station. They questioned me again: “Where will you live? Who do you know there? Do you speak the language?” After answering all these questions, I had to sign a few papers, and then they took me to the bus stop and said, “You must go to Thessaloniki.”

[Read more]

PRESS RELEASES

Again 6 months of waiting for the next court date

Supreme Court hearing postponed

Independent trial report reveals serious errors in the proceedings against Homayoun Sabetara

Homayoun Sabetara will be released from prison!

Media release from 25.09.24

Has the court finally found the key witness?

Media release from 22.09.24

Court fails to bring key witness

Media release from 24.04.24

Single Case or Ongoing Practice?

Media release from 22.04.24

Press Conference on 19 April at 11 am in Thessaloniki

Media release from 16.04.24

24 organisations demand the acquittal of Homayoun Sabetara

Media release from 18.03.24

Human Rights Day

Media release from 05.12.23

My father's case needs attention now

Media release from 16.07.23

Campaign launch #FreeHomayoun

Media release from 22.06.23

PRESS KIT

The press kit provides an overview of the case of Homayoun Sabetara, as well as the #FreeHomayoun campaign and offers relevant information on press matters.

TRIAL OBSERVATIONS

The Undermining of Fair Trial Safeguards in the Trial of Homayoun SabetaraJoint Trial Monitoring Report by the Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMN), European Lawyers for Democracy and Human Rights (ELDH), Feminist Autonomous Centre for Research (FAC) and Legal Centre Lesvos (LCL), 17.01.2025

Joint Statement on Mr. Sabetara’s Appeal Trial

Joint statement by the organisations observing the trial on 25.09.24

Preliminary Report of the trial observers following the Appeal Trial of Homayoun Sabetara

Report of Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMN), European Lawyers for Democracy and Human Rights (ELDH) und Legal Centre Lesvos (LCL) from 23.05.24

Appeal Trial Postponed: Homayoun Sabetara's Case Highlights Systemic Injustice Faced by Migrants Accused of Smuggling

Report of borderline-europe from 28.04.24

Homayoun sabetara's appeal hearing postponed: 5 more months of waiting in prison

Report of Human Rights Legal Project from 24.04.24

Father sentenced to 18 years in prison for driving car with refugees

Report of borderline-europe from 27.10.22

Because a 58-year-old father wanted to join his daughters in Berlin, he now faces 100 years in prison

Report of borderline-europe from 19.09.22

👇 PRESS CONFERENCE OF 19.04.2024 (Part 1) 👇

WATCH THE WHOLE VIDEO ON INSTAGRAM OR LISTEN TO IT AS AUDIO

PRESS

Each additional article helps to draw attention to the case.

If you are interested in further information or interviews, please contact us at nodrivernosurvivor@systemli.org.

The Fire These Times

May 14, 2025

Presented by guest hosts Michelle and Daniel, Cracks in the Walls: Global Perspectives on Migration brings together eight individuals active in migration struggles around the world (Mexico, Haiti, U.S., and Europe) for a discussion on root causes of migration, current and past repression, and, most importantly, impactful approaches to solidarity and resistance.

Cracks in the Walls: Global Perspectives on Migration

Polis 180

August 21, 2024

In dieser Folge tauchen wir in das Thema der Kriminalisierung von Geflüchteten ein. Von sogenannten Schmuggler*innen und Schleuser*innen haben wohl die meisten im aktuellen Migrationsdiskurs schon einmal gehört. Was jedoch dahinter steht und dass Schutzsuchende selbst oft diesem “Schmuggler-Narrativ” zum Opfer fallen, ist hingegen weniger bekannt. Deswegen beleuchten wir in dieser Folge die Mechanismen, die Geflüchtete nicht nur entrechten, sondern auch zu Opfern staatlicher Repression und öffentlicher Vorurteile machen.

Kriminalisierung von Geflüchteten

The Civil Fleet Podcast

April 13, 2024

In this episode we speak with Kiana, Anne, Mahtab and Hannah from the Free Homayoun campaign. Homayoun Sabetara, a widower and father of two, fled Iran to reunite with his daughters in Germany in 2021. Mahtab is one of his daughters. Along the way, Homayoun was forced to drive a car carrying several others across the Greece-Turkey border. He was arrested in Greece, charged with human smuggling, and sentenced to 18 years behind bars at a trial conducted without interpreters. Kiana, Anne, Mahtab and Hannah tell us more about Homayoun's case, his upcoming appeal on April 22, and how Europe's systematic criminalisation of people on the move.

Episode 56: Free Homayoun

Aydentiti

August 15, 2023

Was würdet ihr tun, wenn euer Vater zu Unrecht im Gefängnis säße? Mahtab Sabetara kämpft mit Ihrer Initiative @freehomayoun, um ihren Vater zu befreien. Sie redet in der neuen Aydentity Podcast Folge mit Adrian Pourviseh darüber, wie sie mit Menschen umgeht, die ihren Vater als "Schmuggler" verurteilen.

Von Schmuggel und Fluchthilfe

RaBe

March 11, 2023

In dieser Sendung geht es um Gewalt und um Widerstand. Es geht um die Gewalt an den Aussengrenzen Europas und um die Kriminalisierung geflüchteter Personen, die viele ins Gefängnis bringt. Und es geht um Widerstand dagegen, konkret um den Kampf einer Tochter, die für die Freilassung ihres Vater kämpft, der auf seiner Flucht aus dem Iran in Griechenland zu 18 Jahren Haft verurteilt wurde. Wir hören persönliche Texte und Analysen zur Situation an den Grenzen und zu der scheinheiligen Anti-Schmuggel-Politik. Und zwischendurch Musik von Roody, einer jungen Rapperin aus Teheran.

ZACK - DEIN FEMINISTISCHES RADIO

Medico International

July 27, 2023

In Griechenland sitzen über 2000 Geflüchtete wegen des Vorwurfs des Schmuggels im Gefängnis. Die Prozesse dauern im Schnitt 37 Minuten und das Urteil lautet durchschnittlich auf 46 Jahre Haft.

Knast statt Asyl: Wie die EU Geflüchtete zu vermeintlichen Schleppern macht

3FACH

January 22, 2024

Das Asylsuchen ist zwar ein Menschenrecht, welchen sich die EU eigentlich auch verschreibt, doch um ein Asyl zu suchen muss mensch im Land selber sein, in welchem das Asyl gesucht wird. Doch der Weg zwischen den beiden Ländern ist nicht immer legal, das bedeutet konkret auch, dass die Flucht sehr schnell kriminalisiert werden kann. Was konkrete Forderungen von Organisationen wie Seebrücke Schweiz und Kampagnen wie FreeHomayoun sind und wie die Kampagne entstand, wie auch so einiges mehr, erfährst Du alles in der ganzen Sendung.

Festung Europa und die Kampagne "Free Homayoun"

The Fire These Times

Cracks in the Walls: Global Perspectives on Migration

May 14, 2025

Presented by guest hosts Michelle and Daniel, Cracks in the Walls: Global Perspectives on Migration brings together eight individuals active in migration struggles around the world (Mexico, Haiti, U.S., and Europe) for a discussion on root causes of migration, current and past repression, and, most importantly, impactful approaches to solidarity and resistance.

Polis 180

Kriminalisierung von Geflüchteten

August 21, 2024

In dieser Folge tauchen wir in das Thema der Kriminalisierung von Geflüchteten ein. Von sogenannten Schmuggler*innen und Schleuser*innen haben wohl die meisten im aktuellen Migrationsdiskurs schon einmal gehört. Was jedoch dahinter steht und dass Schutzsuchende selbst oft diesem “Schmuggler-Narrativ” zum Opfer fallen, ist hingegen weniger bekannt. Deswegen beleuchten wir in dieser Folge die Mechanismen, die Geflüchtete nicht nur entrechten, sondern auch zu Opfern staatlicher Repression und öffentlicher Vorurteile machen.

The Civil Fleet Podcast

Episode 56: Free Homayoun

April 13, 2024

In this episode we speak with Kiana, Anne, Mahtab and Hannah from the Free Homayoun campaign. Homayoun Sabetara, a widower and father of two, fled Iran to reunite with his daughters in Germany in 2021. Mahtab is one of his daughters. Along the way, Homayoun was forced to drive a car carrying several others across the Greece-Turkey border. He was arrested in Greece, charged with human smuggling, and sentenced to 18 years behind bars at a trial conducted without interpreters. Kiana, Anne, Mahtab and Hannah tell us more about Homayoun's case, his upcoming appeal on April 22, and how Europe's systematic criminalisation of people on the move.

Aydentiti

Von Schmuggel und Fluchthilfe

August 15, 2023

Was würdet ihr tun, wenn euer Vater zu Unrecht im Gefängnis säße? Mahtab Sabetara kämpft mit Ihrer Initiative @freehomayoun, um ihren Vater zu befreien. Sie redet in der neuen Aydentity Podcast Folge mit Adrian Pourviseh darüber, wie sie mit Menschen umgeht, die ihren Vater als "Schmuggler" verurteilen.

RaBe

ZACK - DEIN FEMINISTISCHES RADIO

March 11, 2023

In dieser Sendung geht es um Gewalt und um Widerstand. Es geht um die Gewalt an den Aussengrenzen Europas und um die Kriminalisierung geflüchteter Personen, die viele ins Gefängnis bringt. Und es geht um Widerstand dagegen, konkret um den Kampf einer Tochter, die für die Freilassung ihres Vater kämpft, der auf seiner Flucht aus dem Iran in Griechenland zu 18 Jahren Haft verurteilt wurde. Wir hören persönliche Texte und Analysen zur Situation an den Grenzen und zu der scheinheiligen Anti-Schmuggel-Politik. Und zwischendurch Musik von Roody, einer jungen Rapperin aus Teheran.

Medico International

Knast statt Asyl: Wie die EU Geflüchtete zu vermeintlichen Schleppern macht

July 27, 2023

In Griechenland sitzen über 2000 Geflüchtete wegen des Vorwurfs des Schmuggels im Gefängnis. Die Prozesse dauern im Schnitt 37 Minuten und das Urteil lautet durchschnittlich auf 46 Jahre Haft.

3FACH

Festung Europa und die Kampagne "Free Homayoun"

January 22, 2024

Das Asylsuchen ist zwar ein Menschenrecht, welchen sich die EU eigentlich auch verschreibt, doch um ein Asyl zu suchen muss mensch im Land selber sein, in welchem das Asyl gesucht wird. Doch der Weg zwischen den beiden Ländern ist nicht immer legal, das bedeutet konkret auch, dass die Flucht sehr schnell kriminalisiert werden kann. Was konkrete Forderungen von Organisationen wie Seebrücke Schweiz und Kampagnen wie FreeHomayoun sind und wie die Kampagne entstand, wie auch so einiges mehr, erfährst Du alles in der ganzen Sendung.

Infolibre

September 19, 2025

Στις 19 Σεπτεμβρίου 2025 θα εξεταστεί στον Άρειο Πάγο, το ανώτατο δικαστήριο της Ελλάδας, η υπόθεση του Homayoun Sabetara. Η αθώωσή του θα μπορούσε

να ανοίξει τον δρόμο για περισσότερους από 2.000 ανθρώπους που κατηγορούνται στη χώρα για το ότι δήθεν «βοήθησαν παράνομη είσοδο».

FreeHomayoun: Πρώτη υπόθεση στον Άρειο Πάγο – πιθανότητα για απόφαση-ορόσημο σε δίκες για φερόμενη «παράνομη είσοδο»

Graswurzelrevolution

May 2, 2025

m 25. August 2021 wurde Homayoun Sabetara, ein aus dem Iran geflohener Migrant, von der griechischen Polizei festgenommen, nachdem er ein Auto über die türkisch-griechische Grenze gefahren hatte. In einem unfairen Verfahren wurde er am 26. September 2022 wegen „Menschenschmuggels“ zu 18 Jahren Haft verurteilt. Seit seiner Verhaftung saß er drei Jahre im Gefängnis in Griechenland. Zum Zeitpunkt seiner Flucht aus dem Iran hatte er keine legale und sichere Möglichkeit, nach Deutschland zu gelangen, wo seine Kinder leben. Am 16. Dezember 2024 wurde er aus dem Gefängnis entlassen. Sein Prozess vor dem Supreme Court wurde auf den 19. September 2025 verschoben.

Das System Knast ist ein wesentlicher Bestandteil der Festung Europa

Alterthess

December 17, 2024

Τρείς μήνες μετά την απόφαση του Εφετείου και τρία χρόνια μετά την άδικη σύλληψή του ως διακινητή μεταναστών ο Χομαγιούν Σαμπετάρα αποφυλακίστηκε και έφτασε στη Θεσσαλονίκη χθες το απόγευμα, ανακοίνωσε η διεθνής καμπάνια Free Homayoun.

Αποφυλακίστηκε ο Χομαγιούν Σαμπετάρα τρεις μήνες μετά τη δικαστική απόφαση

Directa

December 13, 2024

A la Unió Europea, milers de persones migrants i activistes són detingudes i sentenciades cada any a penes de presó. En aquesta anàlisi, expliquem com funciona el sistema legal dels estats membres que persegueix a qui vol travessar les fronteres europees i a qui els dona suport per a fer-ho

Tot el pes de la llei contra activistes i migrants: el delicte de desafiar l'Europa fortalesa

Die Freiheitsliebe

November 29, 2024

Seit mehr als 3 Jahren sitzt Homayoun Sabetara in einem griechischen Gefängnis, weil es auf seiner eigenen Flucht angeblich Menschen schmuggelte. Nach dem Urteil des griechischen Berufungsgerichts hätte er schon frei sein müssen, doch er sitzt immer noch in Griechenland in Haft. Wir haben mit Anne Noack von der Kampagne Free Homayoun gesprochen.

Homayoun Sabetara – Drei Jahre unschuldig in griechischer Haft – Im Gespräch

Missy

November 11, 2024

Der iranische Geflüchtete Homayoun Sabetara wurde in Griechenland festgenommen, der Vorwurf:

Menschenschmuggel, weil er ein Auto mit weiteren Geflüchteten fuhr. Seine Tochter fordert die Anerkennung von anonymisierten Gefangenen, die in einem entmenschlichenden System gefangen sind.

Anonyme Gefangene

BVMN u.a.

October 1, 2024

On 24 and 25 September 2024, Aegean Migrant Solidarity (AMS), the Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMN), the European Lawyers for Democracy and Human Rights (ELDH), borderline-europe e.V., the Legal Centre Lesvos (LCL), and the Feminist Autonomous Centre for research (FAC) observed the proceedings of the Appeal trial of Homayoun Sabetara at the Appeal Court of Thessaloniki.

Joint Statement on Mr. Sabetara’s Appeal Trial

Seebrücke

September 30, 2024

Viel zu lang musste der aus dem Iran geflüchtete Homayoun Sabetara in Griechenland in Haft unter unwürdigen Bedingungen auf seinen Berufungsprozess warten, nachdem er im September 2022 in einem unfairen Prozess zu 18 Jahren Gefängnis verurteilt wurde. Nun fand gestern endlich die Verhandlung statt mit dem Urteil: Homayoun kommt frei! Seine Strafe wurde von 18 Jahren auf 7 Jahre und 4 Monate reduziert.

Nach 3 Jahren Gefängnis: Homayoun kommt frei!

Frankfurter Rundschau

September 27, 2024

Der aus dem Iran geflohen Homayoun Sabetara wurde in Griechenland als Schlepper verurteilt, aber kann nun das Gefängnis verlassen. Sein Schicksal sei „kein Einzelfall“, sagen ihn Unterstützende.

In Griechenland inhaftierter Iraner Homayoun: Angeblicher Schleuser kommt frei

taz

September 27, 2024

Der krebskranke Geflüchtete Homayoun Sabetera saß drei Jahre aufgrund zweifelhafter Beweise in Griechenland wegen Schlepperei in Haft – weil er das Fluchtauto fuhr. Das Kampagnenteam #FreeHomayoun erstritt seine Freilassung. Er ist kein Einzelfall

„Es trifft vor allem Flüchtende selbst“

Moritz Pompl

September 27, 2024

Wer in Griechenland als Schlepper erwischt wird, dem drohen drakonische Haftstrafen. Im Schnitt 46 Jahre. Dabei ist oft nicht klar, ob es sich tatsächlich um Schlepper handelt. Oder um Personen, die selbst auf der Flucht sind. Einer von Ihnen: Homayoun. Ein Iraner, der zu seiner Tochter nach Deutschland wollte. Die hat jetzt versucht, ein Gericht in Griechenland von seiner Unschuld zu überzeugen.

Bekommt Mahtab ihren Vater frei?

Griechenlandsolidarität

September 26, 2024

Homayoun wird aus dem Gefängnis entlassen! Das Gericht hat beschlossen, die Strafe für den iranischen Einwanderer Homayoun Sabetara zu reduzieren.

Das Gericht in Thessaloniki hat bekannt gegeben, dass das erste Urteil des Berufungsgerichts im Fall gegen die Verurteilung von Homayoun Sabetera aufgehoben wurde.

Homayoun kommt frei!

Infolibre

September 25, 2024

Το Εφετείο Θεσσαλονίκης μείωσε την ποινή του Χόμαγιουν Σαμπετάρα, από 18 χρόνια φυλάκιση σε 7 χρόνια και 4 μήνες. Κάτι που σημαίνει ότι έχοντας μείνει στις ελληνικές φυλακές 3 χρόνια, αποφυλακίζεται καθώς έχει εκτίσει τα 2/3 της ποινής. Όπως ήταν επόμενο αυτή η απόφαση σκόρπισε την ανακούφιση όλων των αλληλέγγυων που είχαν σπεύσει προς συμπαράσταση και ιδιαίτερα της Καμπάνιας για την απελευθέρωσή του.

HOMAYOUN FREEd! Ελεύθερος ο Χόμαγιουν μετά από τρία χρόνια φυλάκιση!

Alterthess

September 25, 2024

Θετική εξέλιξη για τον 61χρονο Ιρανό μετανάστη Homayoun Sabetara, πατέρα δύο παιδιών, που διωκόταν με την κατηγορία της «διακίνησης μεταναστών» είχε η δίκη στο Τριμελές Εφετείο Κακουργημάτων Θεσσαλονίκης. Ο Homayoun κρατούνταν στις ελληνικές φυλακές από το 2021, όταν και συνελήφθη μαζί �με άλλους μετανάστες κατά την προσπάθειά του να διασχίσει την Ελλάδα για να συναντήσει την κόρη του στην Γερμανία. Είχε καταδικαστεί πρωτόδικα σε 18 χρόνια και φυλακίστηκε όπως και χιλιάδες μετανάστες στη χώρα μας, αποτέλεσμα της συστηματικής ποινικοποίησης της μετανάστευσης στη Ευρώπη.

Ο Homayoun θα αποφυλακιστεί! Μείωση της ποινής αποφάσισε το δικαστήριο για τον Ιρανό μετανάστη Homayoun Sabetara

Alterthess

September 24, 2024

Αύριο θα συνεχιστεί η δίκη για τον Homayoun Sabetara που διώκεται με την κατηγορία της «διακίνησης μεταναστών». Ο Homayoun κρατείται στις ελληνικές φυλακές από το 2021, όταν και συνελήφθη μαζί με άλλους μετανάστες κατά την προσπάθειά του να διασχίσει την ελλάδα για να συναντήσει την κόρη του στη Γερμανία.

Την Τετάρτη συνεχίζεται η δίκη του Homayoun Sabetara στη Θεσσαλονίκη-Συγκέντρωση αλληλεγγύης στα δικαστήρια

Captain Support

September 23, 2024

As human rights, solidarity, and grassroots organisations providing representation, supporting, and monitoring the trials of criminalised migrants, we know all too well that the prosecution of Homayoun is unfortunately not unique. The targeting of people on the move as smugglers has become a part of migration management in Greece and throughout Europe, and must be stopped.

Free Homayoun and all Criminalised People on the Move!

Infolibre

September 23, 2024

Μία ημέρα πριν από τη δεύτερη προγραμματισμένη εκδίκαση της έφεσης του Homayoun Sabetara, στις 24 Σεπτεμβρίου 2024 στη Θεσσαλονίκη, οι συγγενείς και οι φίλοι εξακολουθούν να μην γνωρίζουν αν ο αγνοούμενος βασικός μάρτυρας έχει βρεθεί. Άλλη μια αναβολή της τελικής απόφασης στην υπόθεση αυτή θα ήταν δραματική για τον Homayoun Sabetara, η κατάσταση της υγείας του οποίου συνεχίζει να επιδεινώνεται.

Εφετείο Θεσσαλονίκης 24/9: Βρήκε τελικά το δικαστήριο τον μάρτυρα-κλειδί;

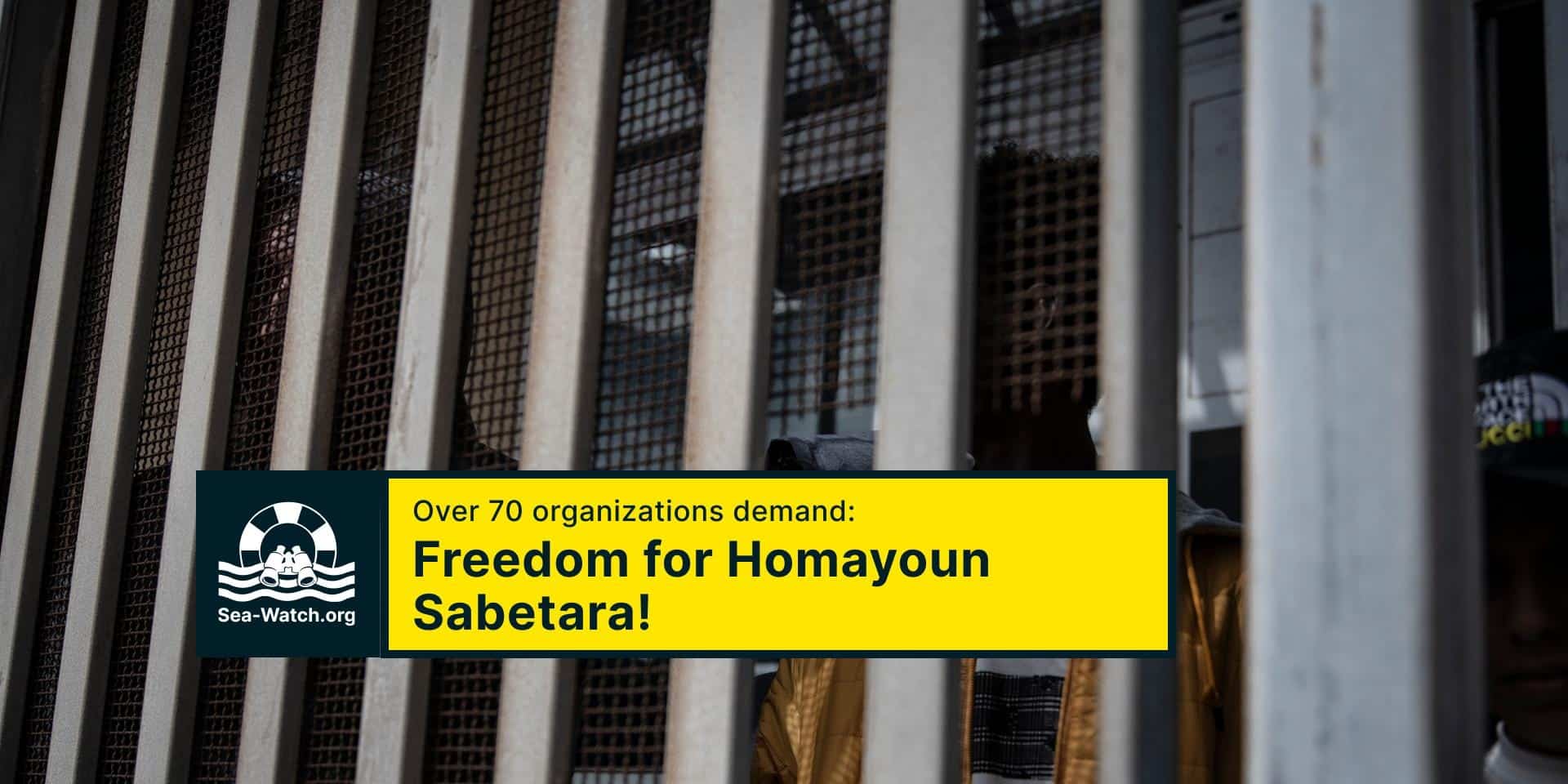

#LeaveNoOneBehind

September 20, 2024

Homayoun Sabetara has been innocently jailed in Greece for more than three years. Like thousands of others, he is unlawfully accused of driving his own getaway car across the Greek border to apply for asylum. Ahead of his appeal trial on 24 September, 70 organizations, including LeaveNoOneBehind, borderline-europe and Sea-Watch, are calling for his release and an end to the criminalization of people on the move in Europe.

Over 70 organizations demand: Freedom for Homayoun Sabetara

Kinimatorama

September 13, 2024

Την Τρίτη 24 Σεπτέμβρη, στα δικαστήρια Θεσσαλονίκης, θα συνεχιστεί η δίκη της υπόθεσης του Homayoun Sabetara, που διώκεται με την κατηγορία της «διακίνησης μεταναστών». Ο Homayoun κρατείται στις ελληνικές φυλακές από το 2021, όταν και συνελήφθη μαζί με άλλους μετανάστες κατά την προσπάθειά του να διασχίσει την ελλάδα για να συνα�ντήσει την κόρη του στην γερμανία.

ΣΥΓΚΕΝΤΡΩΣΗ ΣΤΑ ΔΙΚΑΣΤΗΡΙΑ ΘΕΣΣΑΛΟΝΙΚΗΣ - ΔΙΚΗ HOMAYOUN SABETARA

Özgür Politika

September 12, 2024

55 yılı aşkın süredir dünyanın farklı bölgelerinde savaştan zarar görenlere yardım eden Medico İnternational, mültecilere yönelik artan baskılar nedeniyle harekete geçti. “Hareket Özgürlüğü Fonu” oluşturduğunu duyuran Medico İnternational, oluşturulan kaynakları mültecilere aktaracak.

Merkezi Frankfurt’ta bulunan Medico International ‘Hareket Özgürlüğü Fonu’ adıyla yeni bir mülteci yardım fonu kuruyor. Medico, fonla ilgili kamuoyunu bilgilendirmek için Frankfurt’ta bir tanıtım akşamı düzenledi. Tanıtıma, Frankfurt, Offenbach, Hanau, Darmstadt ve çevre kentlerinden, mültecilerle ilgili çalışma yürüten kişi ve kurum temsilcileri katıldı.

Hareket Özgürlüğü Fonu kuruluyor

Infolibre

September 10, 2024

Λιγότερο από δύο εβδομάδες απομένουν για την εκδίκαση της έφεσης του Homayoun Sabetara. Ένας μετανάστης κυνηγημένος από το κράτος καταγωγής του, το Ιράν. Εξαναγκάστηκε να οδηγήσει όχημα από το σημείο αναχώρησης κοντά στα τουρκοελληνικά σύνορα, στο οποίο επέβαιναν �επτά επιπλέον άτομα και καταδικάστηκει σε μια δίκη παρωδία -χωρίς διερμηνεία, παράτυπα και παράνομα- με την εξαιρετικά βαριά κατηγορία του “διακινητή”. Ο Homayoun Sabetara καταδικάστηκε σε 18 χρόνια κάθειρξη και έχει ήδη εκτίσει τρία χρόνια άδικα.

Mετράμε αντίστροφα για την εκδίκαση της έφεσης του Χομαγιούν και κάθε άδικα φυλακισμένου για διακίνηση

Medico International

August 26, 2024

Im September 2021 erhält Mahtab Sabetara einen Anruf, der ihr Leben verändern wird. Ihr Vater, Homayoun Sabetara, wurde in Griechenland verhaftet und sitzt im Gefängnis. Der Vorwurf: Schmuggel. Für seine zwei Kinder, die beide in Berlin leben, bricht eine Welt zusammen. Wochenlang hatten sie um ihren Vater, ihren einzigen verbliebenen Elternteil, gebangt, der sich auf den Weg gemacht hatte, um ihnen nach Berlin zu folgen. Die beiden Geschwister hatten den Iran aufgrund der schwierigen politischen Situation mithilfe von Studierendenvisa verlassen. Ihrem 60-jährigen Vater war dieser Weg jedoch verwehrt.

Auf der Flucht zu seinen Kindern zum Schmuggler erklärt

Melting Pot

June 22, 2024

«Una rivista per andare al di là dello sdegno, per non porsi solo in posizione di difesa, ma per avanzare»

Giovedì 20 giugno nello spazio “Media & Produzioni” di Sherwood Festival, in occasione della giornata mondiale del rifugiato e a conclusione di una settimana segnata da tragici naufragi nel Mediterraneo e dalla violenta morte del bracciante agricolo Satnam Singh, si è tenuta allo Sherwood Festival la presentazione della nuova rivista di Melting Pot: Controfuoco. Per una critica all’ordine delle cose.

Controfuoco. Il report e il video della presentazione a Sherwood Festival

Controfuoco

June 20, 2024

Mentre la criminalizzazione delle missioni di salvataggio in mare e dialtre iniziative solidali di soccorso ha acquisito di recente una certa attenzione mediatica, la repressione quotidiana delle persone in movimento nell’attraversare i confini continua a rimanere sostanzialmente invisibile. Gli arresti effettuati con l’accusa di smuggling – traducibile generalmente in italiano con “traffico”, o “contrabbando”, nel caso specifico come “facilitazione dell’immigrazione illegale” – dopo ogni passaggio di frontiera sono diventati una prassi comune da quando, nel 2015, l’agenda dell’Unione Europea sulla migrazione ha appuntato la loro repressione come propria priorità assoluta.

La criminalizzazione

della solidarietà dal

basso e la figura dello

smuggler: il caso

della Grecia

Heinrich Böll Stiftung

June 19, 2024

Migration und Flucht stehen in der EU seit längerem wieder ganz oben auf der Agenda. Dabei geht es weniger darum, Probleme zu lösen und das Leid der Menschen auf der Flucht zu adressieren, sondern vor allem darum zu verhindern, dass Geflüchtete ihren Fuß auf europäischen Boden setzen. Das schadet den Schutzsuchenden und dem politischen Klima.

Weltflüchtlingstag 2024: Gegensteuern vor dem Schiffbruch

#FreePylos9

June 14, 2024

In this teach-in, which took place virtually the week before the trial of the Pylos9 began, we were joined by defendants’ lawyers, organisers, and people facing criminalisation to understand how this case has unfolded, and why it is crucial to show solidarity with people on the move criminalised as “smugglers” or “traffickers”. We discussed this specific legal case, linking it to and contextualising it within ongoing practices of resistance to border violence, which is the real cause of deadly shipwrecks.

FreePylos9 Teach-In

El Diario

May 19, 2024

Un año después del naufragio del Adriana, uno de los peores que se han visto en aguas griegas, nueve de los supervivientes se enfrentan al juicio acusados de provocar la muerte de centenares de personas

Cuando nueve supervivientes del naufragio más mortífero son acusados de causar la muerte de centenares de migrantes

borderline-europe

April 28, 2024

Am 23. April 2024 fand die Berufungsverhandlung von Homayoun Sabetara vor dem dreiköpfigen Berufungsgericht von Thessaloniki statt. Nachdem er fast 1,5 Jahre auf die Verhandlung gewartet hatte, musste Herr Sabetara eine weitere Verschiebung um fünf Monate hinnehmen, weil es dem Gericht wieder einmal nicht gelungen war, die Anwesenheit des Hauptbelastungszeugen sicherzustellen. Sein Fall verdeutlicht die systemische Gewalt in Schmugglerprozessen in Griechenland. Betroffen stehen somit vor dem Dilemma, sich entscheiden zu müssen, ob sie ihren Grundrechten Vorrang einräumen, die, wenn sie gewahrt werden, möglicherweise die Grundlage für die Verurteilung zunichte machen würden, oder ob sie unter den gegebenen Umständen so schnell wie möglich das bestmögliche Ergebnis für sich erzielen und dabei ungerechte Urteile und erhebliche Rechtsverletzungen in Kauf nehmen.

Berufungsprozess vertagt: Der Fall von Homayoun Sabetara verdeutlicht die systemische Gewalt in Schmugglerprozessen

Voria

April 28, 2024

Οι επιλογές των κυκλωμάτων να αναγκάζουν μετανάστες και πρόσφυγες να οδηγήσουν τα αυτοκίνητα της διακίνησης από τον Έβρο στη Θεσσαλονίκη - Η αντιμετώπισή τους από τα δικαστήρια και η περίπτωση του 60χρονου Ιρανού

Θεσσαλονίκη: Πώς η καταδίκη ενός Ιρανού για διακίνηση μεταναστών οργάνωσε ένα κίνημα για τους οδηγούς - θύματα

Propaganda

April 26, 2024

Ο Homayoun Sabetara, μετανάστης από το Ιράν, συνελήφθη στη Θεσσαλονίκη το 2021 επειδή οδηγούσε το όχημα στο οποίο τον επιβίβασε ο διακινητής του, και καταδικάστηκε άδικα σε 18 χρόνια κάθειρξης για «λαθρεμπορία». Τώρα, παλεύει για τη δικαίωσή του.

Ο Homayoun είναι ένα ακόμα θύμα των τακτικών ποινικοποίησης της μετανάστευσης στην Ευρώπη

ARTICLES

VIDEOS

Free Homayoun

Pressekonferenz von Free Homayoun

April 19, 2024

Auf der Pressekonferenz werden wir detailliert über den aktuellen Stand des Falles von Homayoun Sabetara informieren, Hintergrundinformationen zur Situation der Kriminalisierung von People on the Move liefern und Einblicke in die rechtlichen und humanitären Aspekte dieses Themas geben. Vertreter der Kampagne und Experten werden für Fragen und Interviews zur Verfügung stehen.

ARD

Schleuser-Kriminalität: Die Falschen vor Gericht?

September 21, 2023

Über 500 Menschen sind im Juni auf einem überfüllten Fischkutter gestorben, der vor der Küste Griechenlands gesunken war. Kurz darauf nahmen die griechischen Behörden neun Ägypter fest, die überlebt hatten. Ihnen drohen lebenslange Haftstrafen. Immer wieder werden in Griechenland Geflüchtete als Schlepper verurteilt, während die eigentlichen Schleuser ungestraft davonkommen. Möglich macht das eine umstrittene EU-Richtlinie.

Borderline Europe

Schmuggler-Portraits: Homayoun Sabetara, 18 Jahre Haft

March 21, 2023

Der "Kampf gegen Schmuggler" ist mit Herzstück europäischer Migrationspolitik. Jedes Jahr fließen Millionen von Euro in den "Kampf gegen skrupellose Kriminelle, die das Leben von Menschen auf der Flucht aufs Spiel setzen", zahlreiche Anklagen werden erhoben, Prozesse geführt, Tausende von Menschen werden inhaftiert. Doch was steckt dahinter? Seit wann interessiert sich die EU für das Wohlergehen Flüchtender?

Borderline Europe

Gala: Berliner Tag des Schmuggels - Festliche Ehrung Europas Schmuggler und Schleuser

June 29, 2023

Von der EU werden Schmuggler*innen dämonisiert und kriminalisiert. Der sogenannte "Kampf gegen Schmuggel" dient als Rechtfertigung für repressive Maßnahmen und den Einsatz erheblicher Ressourcen. Unter dem Vorwand, Migrierende vor Gewalt und Ausbeutung zu schützen, wird dabei oft eine moralische Legitimation vorgegeben. Selbst in Kreisen, die sich für Bewegungsfreiheit einsetzen, hat "der Schmuggler" oftmals keinen guten Ruf.

Flüchtlingsrat Baden-Württemberg e. V.

Vortrag: Flucht als Verbrechen?

September 8, 2023

Am Rande der öffentlichen Wahrnehmung werden derzeit Tausende von Geflüchteten in Italien und Griechenland zu drakonischen Haftstrafen von teilweise 100 Jahren und mehr verurteilt. Diese Prozesse dauern durchschnittlich 38 Minuten und enden für die Angeklagten mit durchschnittlich 44 Jahren Haft. Das Verbrechen ist ihre Flucht, der offizielle Vorwurf „Beihilfe zu illegalem Grenzübertritt“ durch Geflüchtete am Motor eines Schlauchbootes oder am Steuer eines PKW.

%20%E2%80%A2%20Instagram-Fotos%20und%20-Vid.png)